By November 1943, Hitler was well aware of the threat of invasion along the northern coast of France, and yet the Germans could not pinpoint exactly where it might take place. Hoping to thwart the Allies wherever they landed, Hitler ordered Erwin Rommel to finish shoring up the Atlantic Wall, 2400 miles of bunkers, landmines, and horrible obstacles.

In January of 1944, General Dwight Eisenhower was appointed commander of Operation Overlord, the codename for the Battle of Normandy where the Allies would invade the German-occupied western European front. The elaborate and complicated offensive required nearly a year in the planning stages before the invasion finally took place. If the Germans even had two days’ notice of the invasions prime location the mission would be doomed to failure.

During the weeks and months before the invasion was finally set for early June, the Allies carried out an elaborate deception scheme. Operation Bodyguard consisted of two parts: “Fortitude North” which was intended to make the Germans believe the attack would commence in Norway and, “Fortitude South” which would convince the Germans to watch the area just northeast of Normandy in the Pas de Calais.

The Allies fed the Germans a stream of misinformation, both through radio chatter and detailed reports supplied to double agents. To create the illusion that there was a massive buildup of troops and material in southeast England, the Allies deployed a largely “ghost” army. To fool German aerial reconnaissance, artists created inflatable tanks, dummy aircraft, and even fake landing craft which upon closer inspection consisted of painted canvases pulled over frames.

D-Day is how we commonly refer to the June 6th invasion, and yet the term D-Day is actually a reference to “Day-Day.” The exact date that the planned invasion would commence had to be fluid because conditions at sea, weather, and visibility were all critical variables determining the most opportune time to launch the attack. A very full moon would be the cherry on top.

A launch time somewhere between low and high tide was key; ideally with the tide starting to come in. If the tide was low enough, two important aspects of the launch would succeed. First, the amphibious crafts could access and land on the beach, and second, the German obstacles or mines would be visible. The downside of a low tide was that it created a much longer stretch of beach for the soldiers to cross after landing.

The complex invasion plan assigned the British forces to land to the east on beaches code-named Sword and Gold. The Canadians would invade at Juno Beach, and the Americans at Omaha and Utah Beaches.

A wicked storm on June 4th forced Eisenhower to poll the other Allied leaders about whether or not to continue with the original plan to invade on June 5. Some wanted to postpone the launch as much as two weeks. About half voted to wait, half to go.

Ike knew that momentum was building – to delay the attack would lower troop morale and give the Germans time to figure out the Allied plan. Also, and most importantly, there was no Plan B – the landings at Normandy must succeed. Eisenhower decided to delay for 24 hours, hoping that the weather would somehow improve.

It was not to be. June 5th dawned with continued gale force winds and high seas. It was once again up to Ike to make the decision to launch, and after the meteorologists weighed in, he finally gave the go-ahead for Operation Overlord to commence on June 6th.

Once Eisenhower made his decision on June 5th, he drafted two documents; one a formal statement of encouragement and thanks released to the soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the Expeditionary Force on the eve of DDay. The other, a handwritten missive taking full responsibility should the mission fail as he expected it would.

In the first powerful statement, one section jumps out at the reader. He writes, “The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazy tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.” These goals were certainly no small task for those facing participation in the offensive yet they must have felt connected, inspired to play their role in the success of such a noble mission.

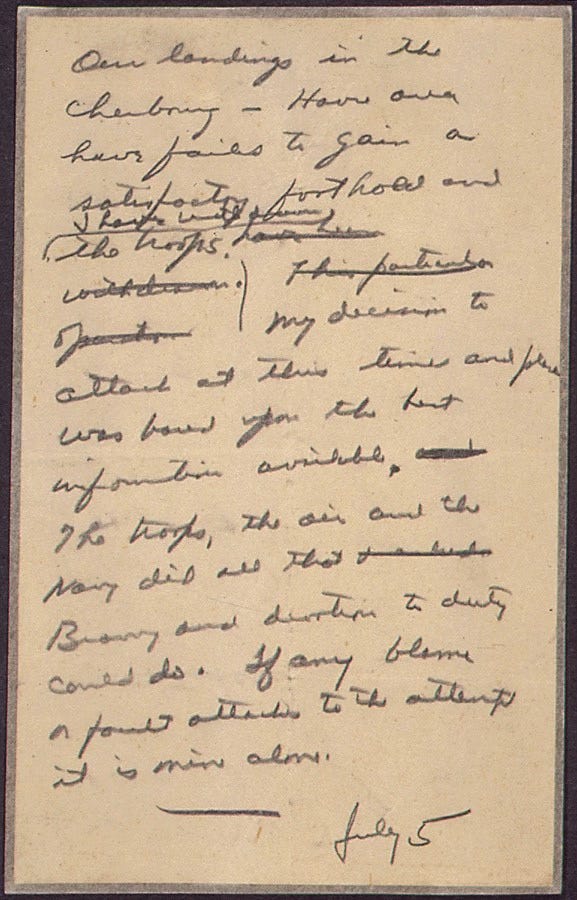

In contrast, the text of Ike’s scratchy handwritten note reads: “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

According to D-Day Overlord, after the success of Operation Overlord, Eisenhower disposed of the note. His secretary later retrieved and saved it.

The National WWII Museum displays this important artifact in a unimposing frame with a simple placard below it. When you stand in front of this seemingly small physical piece of history, you are reminded of the great and terrible responsibility that rested on Eisenhower’s shoulders. In his hands was the largest amphibious invasion in history, the lives of roughly 150,000 men, and the fate of the free world.

What a powerful piece. Perfectly positioned for this moment in history.