The episode's topic focuses on discussing the symbol and history of Rosie the Riveter, an icon from World War II that represents the women who worked in factories and shipyards during the war. Show hosts Mary Ellen Page, Angélica Cordero, and Carys Caffarel dive deep into the story of the icon. They discuss her influence, public perception, the realities faced by working women of that era, and the modern relevance of Rosie, discussing at length how her image transcends race and gender lines. The hosts tackle interesting questions centered around Rosie's legacy and influence in terms of female empowerment, women's rights, and labor rights, as well as how she was portrayed and remembered in post-war culture and even today, providing a deep dive into this female symbol from different perspectives.

Links

Read more here about the story behind the Norman Rockwell Rosie the Riveter painting showcased on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post.

From Arizona State University News: World War II studies program inspires friendships, podcast

Transcript

[00:00:00] Mary Ellen Page: Hello and welcome to World War S.H.E., a podcast that shares the human experiences and the forgotten aspects of World War II that rocked the world then and echo today. I am Mary Ellen Page and I'm here today with Angelica Cordero and joining us for the first time is the effervescent and enigmatic Carys Caffarel.

Carys is a archaeologist sometimes, and she's also responsible for our Instagram page. So, hello and welcome, Carys, and tell us a little bit about yourself.

[00:00:33] Carys Caffarel: Well, thank you so much. That introduction was beautiful. As you just said, my name is Carys Caffarel. I was born in England and moved to Texas when I was seven. I guess as an adult I can say that was probably where my interest in learning about the same topic, but from different perspectives really came into play. ‘Cause man, talk about a culture shock. but I ended up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana where I got my undergrad degree in anthropology from LSU. Then ultimately my master's in World War II studies from ASU. My relationship with World War II is honestly one of happenstance with my background being in archaeology. So working directly with artifacts and being hands on is definitely how my love of history has really grown. Just finding the bigger picture and the story behind what I've found. My dad actually happened upon a job listing for an internship with the collections department at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. Where I actually ended up getting it. I stayed there for almost three years and my time there is how I actually found out about the grad school program And it all just snowballed from there, meeting you ladies, creating this passion project and just letting it rip, seeing where it goes.

[00:02:03] Mary Ellen Page: And it's gone a lot of places, actually.

[00:02:06] Carys Caffarel: It sure has.

[00:02:08] Mary Ellen Page: Yes. I think when we all found out that Carys had actually worked at the World War II Museum, which for many of us is our mothership, we were delighted and she's been able to get us some hands on viewing of the artifacts. I just still remember when we were able to do that, but thanks to you. So that was a truly exciting day.

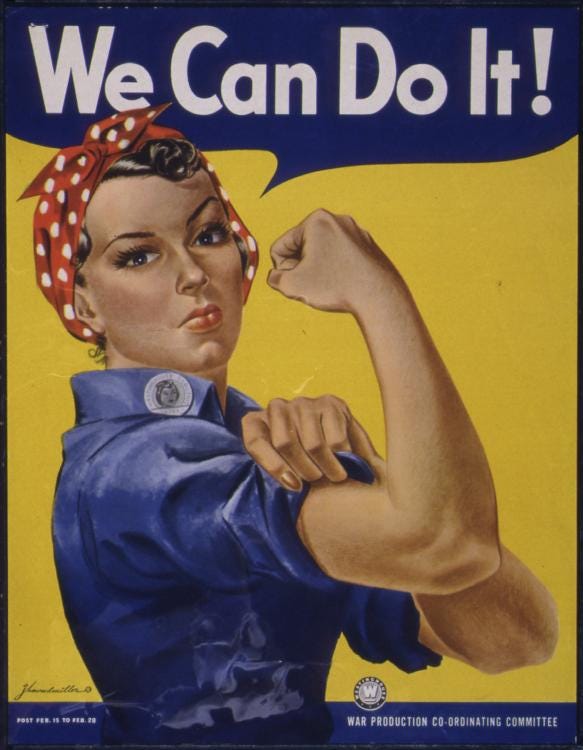

We're just so glad that you're one of the Rosies. We call ourselves the Rosies. That's kind of the name that we gave ourselves. And it just so happens that in this, our third episode, we're going to be talking about that iconic and multifaceted image, Rosie the Riveter, the image and the story behind it. While doing research for this podcast, we realized how deep the story of Rosie the Riveter is and it didn't start with the now famous poster that says, We can do it. It actually began when Red Evans and John Jacob Loeb wrote the song Rosie the Riveter and it was made famous by the Kay Kaiser band. It became a national hit. And so the, the idea of Rosie the Riveter kind of came into the consciousness of America around 1942. So, ladies, where should we begin with, with all of this?

[00:03:17] Angélica Cordero: Well, I think it might not be a bad idea to revisit what the visual of this poster that we are talking about looks like. Rosie the Riveter, as we have seen her, she is a female factory worker who's flexing her muscle and she's looking over her shoulder a little bit. Like, she's got this, I don't know, face she's like stern and knows she's about business.

And she's wearing her blue jean work suit. And she's got her red polka dot bandana. Right above it is the speech bubble where it says We Can Do It and it's on a yellow background. So if you haven't seen it, that's pretty much what it looks like.

[04:07:14] Carys Caffarel: In a nut shell. Um, Google.

[04:08:38] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, Google it real quick.

[00:04:11] Mary Ellen Page: Well, actually a little bit of trivial trivia about the bandana. We see it as the red and white polka dots, but actually some of them were called ordinance scarves because depending on the ordinance factory they were working in, they would have the logos of that ordinance group on that, iconic handkerchief. Well, not a handkerchief.

[00:04:33] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, it was a handkerchief. I would say so, yeah. We need to definitely get our own set of ordnance, quote unquote, ordnance red bandanas for the Rosies themselves.

[00:04:47] Carys Caffarel: Christmas present!

[00:04:48] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, right? But the poster was made in 1942. It was commissioned by Westinghouse Company's War Production Coordinating Committee. They hired Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller in creation of a series of posters. So actually, Rosie the Riveter, the We Can Do It poster that we know, is actually one of several that were actually created by Mr. Miller. I know I had mentioned this in that very first episode about what it came to symbolize for me, and I know Mary, you said that as well. I am curious for Carys to weigh in on what Rosie as an icon, what she symbolizes for you.

[00:05:31] Carys Caffarel: For me personally, I think it's definitely just a woman of strength. She has pride in her convictions. She does what needs to be done without having to be asked. It's just making sure all the cogs in the machine, no pun intended, are just running as smooth as possible because that's what makes the world go round, right? That's what helps everything go smoothly for everybody and even herself. So just, just a really strong woman.

[00:06:04] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, if you search on Google, I think that the results that come back when you search “Rosie the Riveter” are kind of ridiculous. At least the number of them is in the billions and it's no surprise [that] usually in conjunction with any depiction of her, you always see people discussing “She's a symbol of female empowerment, of feminism, of women's economic power, women can do anything, da da da da.” I mean, there are Halloween costumes, which is nuts. Beyonce broke the internet a few years ago by dressing up like her. And there are huge events where people celebrate a full day, where crowds gather together and they're actually dressed like it. So, she's actually become a really massive icon.

[00:06:55] Mary Ellen Page: Much more so than during the war. And this is, I think, something people don't realize. The famous Rockwell picture, painting of Rosie the Riveter that was on the May 1943 cover of the Saturday Evening Post was another iteration of the Rosie idea. And interestingly enough on the We Can Do It poster, nothing says Rosie, but on the Rockwell picture her name is on her lunchbox. She's also standing on top of a copy of Mein Kampf. And so there's really two pictures that we associate specifically with Rosie the Riveter. Those two pictures weren't as iconic then as they are now. But that doesn't diminish what Rosie the Riveter stood for during the war itself. Maybe they didn't call themselves Rosies, but maybe they did, but in terms of how it changed the war and how it changed women in the workplace is really significant.

[00:07:56] Angélica Cordero: If you were to ask other women in your life who aren't Rosies, us Rosies, or other females that we know in the program, how would they respond to who Rosie is to them?

[00:08:11] Carys Caffarel: So, I was actually pretty curious about that. So, a couple nights ago, I just kind of texted a bunch of my friends. I would guess ages, let's say, 26 to 32. I said, “Hey, do you know who Rosie the Riveter is within the context of World War II? But also, what does a modern Rosie look like to you?” So it's pretty interesting.

A lot of the people said almost the same thing for the first question, but the second one is really where it starts to get interesting. So some of the responses to the first question is who she was during the war. One person said, “Rosie the Riveter is an icon that I think most people would recognize. Her red bandana and denim shirt are iconic in front of the yellow background. To me, she symbolizes strength, determination, and hope.”

Somebody else said, that she doesn't know much besides the iconic pose, which is fine. At least she knows who she is, right? That just kind of speaks to her, to Rosie's presence.

Somebody else said, “I seem to remember learning it was propaganda to encourage women to take up the labor force while men were enlisted.”

And lastly, somebody said, “I know that she has the very famous poster of her flexing in a jumpsuit with the red lip. To my understanding, the image was a piece of propaganda during the war for women empowerment, essentially inspiring and motivating women to take on industry jobs while men were off fighting in the war. And I know from this women of all different demographics and backgrounds realize their worth and how the world could go on even without men doing the normally male dominated jobs. And I know after the war. This empowerment movement was essentially wanting to be reversed by a lot of the men because women found their worth in working for themselves and having a job and realizing that they have more than a purpose of just getting married and having kids.”

So I think that's pretty powerful stuff.

[00:10:22] Angelica Cordero: What's really interesting about that is most of them, well, first off, most of them pegged it for propaganda. Which is great because we do know that it is a piece of propaganda but the irony is that it was an internal poster for specifically Westinghouse and was only displayed in Westinghouse factories for a very brief period of time. We're talking about weeks. So this poster that has become such a beloved image to us now was not what it was during the war period. It literally was shown in a handful of places, which means that only a few people actually saw. It's so wild to me to know that and to recognize how different that narrative is by comparison to what we understand of her now.

[00:11:23] Mary Ellen Page: And I also think it's interesting because when we think of Rosie the Riveter, we think of the World War II women's workforce, but but as you said, this wasn't a recruiting poster. It might have been a recruiting poster within Westinghouse, but it was more of a “Keep up the good work!” kind of a “We're behind you!” kind of a thing.

And I find it interesting because even though we I think people then you kind of attach that to the success of women joining the workforce during the war and that's not really true. I actually have the copy of the Saturday Evening Post with her on the cover and there is not one mention of Rosie the Riveter in the entire magazine. And yet there's advertising and there's articles that are encouraging women to join the workforce with no reference to Rosie whatsoever.

[00:12:11] Angélica Cordero: I am a hundred percent in agreement with you in being somewhat shocked by how we think of her now by comparison. In preparation for our recording today, I was looking online and reading through some things and writing some notes down. In all honesty, the number of websites, even official military ones, even official governmental ones, like Library of Congress style level. I'm not saying necessarily the Library of Congress itself, but several reputable websites claim that Rosie the Riveter was a household name, and I basically lost my shit because it was not. She was not. It's so not true and yet here we are. We have these major organizations and reputable places, reputable sites, that are basically perpetuating this myth of who Rosie was and the true story behind the poster itself.

[00:13:22] Mary Ellen Page: And I think it also then diminishes the actual reasons why women joined the workforce during the war. Of course, Rosie is a tremendously good symbol, especially how we have created it for today.

But I think we need to talk about what happened to women during the war. The National War Labor Board said they began enacting statutes that required employers to pay female workers the same wages for male workers and this was specifically for war work. I think that was something that was so appealing, to a lot of women because they were going to get paid. Especially since if they had a partner at war, they were financially more strapped than they would have been if they'd been at home working.

[00:14:09] Carys Caffarel: So I just wanted to backtrack real quick before we got too deep into the next sort of facet of the episode. I just think it's so interesting how the Rosie we know today is not the intended interpretation of the poster, or even what it really meant. […] It speaks a lot to generational glamorization, right? Because one thing I learned when we were in the program was it is actually really hard to look at events of the past without today's context. A lot of people are not historians. They don't really want to go super deep into the topic. And I think somehow, that's how the narratives just get so distorted because people aren't able to look at the event, in this case, Rosie, and look at it with the context of during the war because we're not there, right? We don't know what the environment was, what the stimuli were, how difficult it was for these women, the recruitment process, anything. So I think that's what I love so much about, I guess, us talking about this today is we can kind of almost set the record straight and maybe untie some of these knots and realize that some of these storylines are not as woven together as they should be because something means something very different than what we know.

[00:15:42] Angélica Cordero: I do think that the other aspect to this is when women are left out of the narrative of history, not just as a part of the history itself but as the people telling those histories, it is incredibly difficult to ensure that the narrative, the accuracy of the original narrative continues, right? And so many women, just as much as men, did not talk about their experiences during the war. So many women also post-war did not talk about their experience. And so I think that's the the other element of that. when you get into the details of this history of the real history. It makes me love the Rockwell one a million times more. Mary, can you explain to the audience what it looks like? I think you have a probably better understanding of it in detail than I do. I don't know about you, Carys.

[00:16:43] Mary Ellen Page: So, I love the Rockwell rendition of Rosie. So this Rosie has her arm up like the other one, but in a different direction. She's holding a sandwich. She has buttons all over her overalls. Of course, the V button for victory. Of course, she has a riveting gun draped across her lap with a lunch box that says ‘Rosie’ on it. To make it even better, she's standing on a copy of Mein Kampf. It's just a beautiful, just this confident young woman having her delicious sandwich and stepping on the Germans of Nazi Germany.

I think it's a really effective portrayal. The interesting thing is though, as I was doing some research on this, one of the reasons why this Rosie didn't take off was there was some worry that because ‘Rosie’ was used on the front [of the] lunchbox that the writers of the Rosie the Riveter song, who created the term Rosie the Riveter, might sue.

So, Rockwell gave it to the U. S. government to use for fundraising and that kind of thing, but it really wasn't used again like the other poster. It wasn't used to recruit people to work. It was more of a symbol of the woman who is already working.

We were talking earlier about how nobody really knows the real history of Rosie the Riveter. It didn't stay with the artwork. It didn't stay with the story of World War II. And I think part of that reason is, and I really feel like it's because it was a woman's story. That after the war, it was so dominated by the winning of the battles and the heroism and the incredible stories. And yet these women at home who were building aircraft carriers and machine guns that their story has been very much not told.

[00:18:34] Carys Caffarel: And it's probably because the end goal was reached, right? It's almost like it doesn't really matter how we got there, but the allies won. Victory was had. And so people, like you just said, focused on that because obviously it was a good thing. Usually a lot of the times the people who got us there are just not really talked about.

[00:18:57] Mary Ellen Page: Exactly. And here's the thing, when you think about it, and I'm talking about just practically, we started the war in 1941, but we were not the most powerful military in the world and they needed to get stuff done fast. And I think that's why with so many of the men being shipped overseas it did create these huge gaps. I don't want to use the word used until they won the war. But [women] came through and they helped win the war.

[00:19:29] Angélica Cordero: Well, we didn't, we didn't start the war,

[00:19:32] Mary Ellen Page: Right, exactly.

[00:19:33] Angélica Cordero: But we came into the war.

[00:19:36] Mary Ellen Page: Did it make, did I…?

[00:19:38] Angélica Cordero: I wanted to make sure everybody knows Mary knows we did not start World War II. Believe me, I know she knows.

[00:19:45] Mary Ellen Page: Thank you, I'm really relieved that made completely clear.

[00:19:52] Angélica Cordero: The Rockwell Rosie, and I know we've talked about this before, that the reception was actually also not very positive, largely because Rockwell depicted her as kind of a burly woman.

[00:20:07] Carys Caffarel: Mhm. In men's clothing, baggy overalls, it looked like she was almost wearing men's loafers, thick socks, stuff like that, yeah.

[00:20:17] Mary Ellen Page: And her arms are muscular. Actually on her arms she has this like inch thick leather bracelet on and it's very masculine.

[00:20:29] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, that photo actually reminds me a lot of a very popular black and white photo from 1932 That's called Lunch Atop A Skyscraper. It's basically this long steel bar with a bunch of guys as their eating lunch, right? And to me, it's so perfect. It's so all about what for me now, Rosie means. A woman who was very dedicated, who had one of her guys, or several of her guys, and her guy's friends, and all that other stuff, all out in the war, and she wanted to do everything that she could in her power to actually go and do it. And it wasn't about burly strength or anything having to do with needing to be made up or anything like that. There was a job to be done and I needed to get up in the morning and I needed to do all the things I needed to do and get there and get it done. The irony about this about the reception towards her being kind of muscular is that there's another poster. There's another war poster out there where it's another woman and she's doing the same Rosie flex and she's got a big muscle and it's another war recruitment poster. I don't know if the reception for that was the same, but I just find it really ironic.

[00:21:51] Mary Ellen Page: Well, there was another Rockwell cover that depicted a woman running, and she had all this stuff hanging over her, working stuff and home stuff. It was basically, she was doing everything, and it wasn't as popular as the Rosie cover, but I think it more accurately depicted what an actual Rosie was going through. Just because they were working doesn't mean they didn't have to raise their children and make sure the house was maintained and all of that stuff. And so, in reading about this, all these women were doing co-ops. They were sharing babysitting and meal planning and that kind of stuff.

[00:22:28] Angélica Cordero: Which isn't a far cry from what we're doing today. Let's be real. Yeah. What is your perception of the comparison between the two posters?

[00:22:42] Mary Ellen Page: What do you mean? Do you mean like in how they're interpreted and how they're…

[00:22:47] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, what strikes you if they were side by side next to each other?

[00:22:51] Mary Ellen Page: Yes, okay. So what strikes me is in the We Can Do It poster, it's just her and her arm and her bandana, right? It's a much more, it could be applied anywhere. But the Rockwell cover has her with a rivet gun on her lap and eating her lunch and actually depicting Rosie at work where the other one is depicting Rosie triumphant or trying to say, “Look what we can do.” Whereas, the Rockwell is more of a “Look what I'm doing.” And so, that's kind of how I look at both of them. I prefer the Rockwell one just cause I've always loved Norman Rockwell, but I do love both of them. Also, I have them both in my office. I think that they're both really fairly iconic. I mean that it's no surprise that they're iconic.

[00:23:41] Carys Caffarel: Yeah, I would agree with that. I think they both definitely exude strength, but in almost very different ways. Because the first one, the one we know with the yellow background, she's full face of makeup. Her hair is beautifully done. Her clothes are clean. I think that's more of the idealized version of or perhaps what people thought women at work might look like versus the Rockwell where she's kind of dirty. You can tell she's on her lunch break. She's eating a sandwich.

[00:24:14] Mary Ellen Page: She has goggles on her forehead. One of the people that was commenting about this cover said that the absolutely American penny loafer is what she's wearing standing on top of this copy of Mein Kampf. It's not just this woman. This is America. Both [of the posters], I think, tend to try to promote the American part of it as well.

[00:24:36] Carys Caffarel: For sure.

[00:24:38] Angélica Cordero: Ironically though, the social landscape in which both of these came out wasn't one of women are just coming into the workforce all of a sudden for the first time, right? In 1941, 12 million women in the country were already working. That's a lot of women to be at work December 1941. That means we haven't even gotten into war itself. We haven't even started really truly actually sending our boys to war and 12 million women were already at work.

[00:25:16] Mary Ellen Page: And most of them even during the war itself, when these women were going into the factories, most of them were not doing factory work either. Something that neither of the posters or neither of the artworks depict [that] there were minority women also working. There were African American women. There were Hispanic women. There were Asian women. And I think it's really important that we remember that this was an extraordinary time [when] minorities were given a little bit more leeway to get work and to get paid for it.

[00:25:48] Angélica Cordero: Well, and the other thing too is a large majority of those 12 million women that were already at work were minority women, let's be real. The other interesting thing that I always find really fascinating, and I absolutely love, is the fact that we kind of overlook the fact that prior to the war, in the decade prior, we were struggling from the Great Depression. it totally gets forgotten when we start talking about the Second World War. And largely throughout the 1930s, women were made to feel like crap if they were working. It was basically a big no no. They poo pooed that idea massively. Largely because it was kind of the same idea of what the reception of working women was after the war. “Oh, you're taking jobs away from the guys. How dare you do this?

[00:26:44] Mary Ellen Page: You're taking jobs away from the hero guys.

[00:26:48] Angelica Cordero: Oh, yeah. Well, that's the one major difference from before the war to after the war, right? Because in the ‘30s, it was just a matter of the working man needs to work. There's so few jobs, right? There were so few jobs then that that's what it was. And perception too in the American public towards working women was not good either. More than 80 percent in 1938 were opposed to opening the workplace to women. That's a large majority of the public. And then we're talking two and a half years later the that we're at 12 million women in the workplace. So, obviously ten years has passed since the crash in ‘29, right? And women have still, despite what everybody said, been able to actually maintain jobs. So then, what ends up happening is Pearl Harbor happens, and all of a sudden, we're thrust into this war and women were actually working what kinds of jobs then? What were the jobs that they were typically working?

[00:28:06] Mary Ellen Page: You mean before the war?

[00:28:06] Angélica Cordero: Well, let's say like right around that time because industry hadn't made that shift from not being a war production industry to then being war production industry.

[00:28:17] Mary Ellen Page: So, are we talking about teachers and nurses? Even though then it wasn't as prevalent, but those were the occupations, at least professional occupations. I'm sure there was a lot of domestic work, especially among the minorities. Probably, retail or restaurant work.

[00:28:34] Angélica Cordero: Hmm.

[00:28:34] Carys Caffarel: Secretarial. All that kind of stuff.

[00:28:37] Angélica Cordero: Right, laundry, they were cleaning. For black women, many of them were sharecroppers still as well. So then once the war opens up and all these guys are sent overseas, then all of a sudden this is where the propaganda enters. And we start seeing an influx of “She can do it!” and, I forget what some of the other ones are. “Come and do the job that he left behind.”

[00:29:07] Mary Ellen Page: Right, right. “Stand behind him by working in his job.”

[00:29:12] Angélica Cordero: Yeah.

[00:29:14] Mary Ellen Page: It’s fascinating but I think it also exemplifies the massiveness of the war, right? I mean, we didn't hear all about this during World War I. [… O]f course women helped during the Civil War[…] But when you're talking about the sheer number of soldiers needed and how that basically very much caused a huge a deficit in U. S. at home employees. And I think just the sheer size of the war itself, created this situation.

[00:29:46] Angélica Cordero: What's ironic to me is that they had just spent the last decade being harangued for working. And then all of a sudden were thrust into a war and “Oh my god, we need you” and “We need you to come in” and “We can't do it without you” kind of thing, right? I actually pulled a really great quote I wanted to share with you both.

So [it comes from a book called Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States written by Alice Kessler-Harris. The quote comes from economist Theresa Wolfson in 1942. She says,

It is not easy to forget the propaganda of two decades during the Great Depression. Even in the face of national emergency, such as a great war. Women themselves doubted their ability to do a man's job. Married women with families were loathe to leave their homes. Society had made so little provision for the thousands of jobs that a homemaker must tackle. And when they finally come into the plants, the men resent them as potential scabs.

[00:30:53] Mary Ellen Page: That's a great quote.

[00:30:55] Angélica Cordero: I saw that today. And it captivated me. It was the first time that I had really seen anything that came directly out from the period that really so clearly expressed what many women felt [at that time].

[00:31:14] Mary Ellen Page: And it continued during the war that they were still fighting with men who were in the American factories and who were not trusting them and not believing that they could do what they were doing.

I think something else that's really interesting too here is that once the war was won, post war was this boon of suburbia and homes and that kind of thing. And it's so interesting because in television and in movies, it was about the man being able to make enough money that the wife could stay home and raise the kids. And it kind of reinforced this whole female at home doing the kids and the cleaning and the cooking. And so they had this like little adventure during the war, but it was, in terms of maybe society or in terms of even literature and film, they kind of reinforced women giving these jobs up to give them back to the men who left them when they went to war.

[00:32:17] Carys Caffarel: Well, yeah, because nobody likes change, right? If that's, if that quote unquote worked before then there was no reason why theoretically it shouldn't work again. But I think women having this taste of learning that they can do so much more than, for lack of a better term, the box that society had put them in, they weren't gonna let it go. They weren't ready to.

[00:32:40] Angélica Cordero: Well, and the truth of the matter is, is that the narrative we know about post war women is the one that you're talking about. But in reality, that was not the case. Actually, many women wanted to stay working and were very upset when they basically were either fired or, they were basically fired. They were given a pink slip, literally.

But the really interesting factoid, specifically on the what we're told happened and versus the factual. So if you actually look at labor statistics at the end of the war, the statistics themselves, they do kind of allude to [the idea that] “Oh, women were just going straight back into the Correction: homeworkforce and “Oh my god, six million people lost their jobs because the war ended,” da da da da da. But, the fact of the matter is, is that 3.25 million left work or were laid off in between September 1942 and November 1946, but 2.75 million went right back into the workforce. So there's almost a counterbalance of the number of people who lost their jobs and then immediately got into a new job. Now, they weren't working the same kind of job. Some were but it was so far and few between. But they were still working.

[00:34:17] Mary Ellen Page: And I think also the boom after the war in the fifties, there were jobs. I mean, there were jobs to be had. There were manufacturing jobs, there were all of those jobs because the economy was doing so well. They needed employees. not as if all these men were coming back from the war constantly. By the end of the 40s, I'm sure most of them were back in the States and back in jobs.

[00:34:42] Angélica Cordero: Well, and I think a lot of people had the luxury of securing better paychecks during the war period. Most of the industry work was an average 40 percent higher than most of the consumer jobs that many women were working. So they were getting a lot more money. That's the other thing. And granted, the other thing we have to also consider when saying that is that inflation was very high during that time frame, because remember, we had to pay for a war. So, the crazy thing is they still had so much money. Much more than what they had prior. especially with the Great Depression, right? And so there are some really wonderful quotes from Black women that you'll read that they talk about how they have to thank Hitler for getting them out of the house and into a working factory. The war really shifted a lot of their lifestyles in major ways by taking them off of the farm or in a domestic situation. Or for Mexican American women who were also cleaners or who were seamstresses or who were field workers and canneries. They were also getting out of those environments and being put into these factories or into other manufacturing jobs that were much cleaner and much safer.

[00:36:12] Mary Ellen Page: When you [consider] the Depression era, the public works where they were creating, dams and roads and spreading electricity throughout the country, then you're actually talking about as part of a modernization, not only of the country, but of the workforce.

And when you think of all of the innovations that were done just in the factories to create these massive ships and planes and weapons, they were modern. So, it was really the beginning of a lot of modernization of the workforce, but also of the type of jobs that people had.

[00:36:48] Angélica Cordero: Don't get me started on talking about shipyards, because I will talk shipyards all day long. I love Kaiser. I love the fact that he did prefab. What's crazy to me is that I liken him to IKEA, which I know is really crazy because [t]he systems are not the same. Like, why would I think it?

Mary Ellen Page: And they don’t have the meatballs?

Angélica Cordero: I know, right? But for some reason or another, I'm [think,] “Oh my God, everything's prefabbed. He figured out a process. He took the Ford system.” I mean, I get nerdy about about the Kaiser system. It's

[00:37:24] Carys Caffarel: Yeah. But we love that that's how your brain works. I mean. Remind us to talk at one point about Thanksgiving. We got a great little story about, about that.

Angelica Cordero: Oh, that one’s one of my favorites.

Carys Caffarel: We digress slightly.

[00:37:38] Angélica Cordero: You're right that so much changed, and within labor too that honestly gets so overlooked in feminist studies or women and gender studies. [They] look at this period and they think that women just kind of like threw their arms up in the air, and “We're not going to care anymore about fighting for our rights”, and “Everything is going to be all about the dudes and the war,” and it's so not true because they lobbied. [They] became members of the union after a really hard time of being kept away from being in the Union. They fought to be in the Union, and then once they're in Unions, what are they doing? They're also fighting for their rights. The fact that they were able to get Congress to pass an act to support the creation of federal[ly] funded child care facilities is insane to me in this day and age. And yet in 1942, women were able to do that.

[00:38:44] Mary Ellen Page: An yet we’re still fighting for it today. We still haven't resolved it. We may have started it, but it is not resolved.

[00:38:50] Angélica Cordero: Imagine trying to have a conversation, an argument for and in favor of federally funded childcare now. People would crucify you and yet then, that was only one thing that they lobbied to get and were able to secure. You mentioned the pay equality in 1942 that they were able to get. There were special provisions because they were considered such a vital labor resource. That companies created these fancy extended grocery hours. They had on site childcare. They also had cafeterias. So that you literally could get off of your shift, walk into the cafeteria, and have food to pick up, hot food to take home.

[00:39:40] Carys Caffarel: I think it's interesting what you just said though, that, perhaps all this was able to happen to be and be facilitated because, you just said that essentially women were viewed as a labor resource, Rright? So it's not the fact that they were women and they were trying to make all these advances for themselves. It's that they were needed and companies wanted to do what they can to ensure that they get the work done. So I think perhaps that's maybe not why it's been carried so far into modern times and now because it's not viewed the same way. It's viewed as women fighting for something as a woman, not just a labor resource.

[00:40:23] Mary Ellen Page: Well, and also the sheer amount of women that had children that were working. This was then this was an immediate need. I mean, it's not that it happened over a couple of years. They had to deal with it immediately because all these women with children were getting jobs and then you have babysitting issues food, everything. It forced a them in, not completely, but in some ways, to make provisions so that these women could work longer hours and more dedicated because they weren't worrying about cooking 15 meals or whatever.

[00:41:01] Carys Caffarel: Exactly.

[00:41:01] Angélica Cordero: Don't you know a war is at hand?

[00:41:03] Mary Ellen Page: Don’t you know we're at war?

[00:41:06] Angélica Cordero: What you brought up that makes me chuckle is that, Yeah a ton of women then had lots of children, or were new moms. Well, I mean, someone was rushed to the altar. Lots of people were boinking and having babies.

[00:41:26] Mary Ellen Page: And having rushed marriages before they were deployed, that kind of thing.

[00:41:30] Carys Caffarel: Mm-Hmm.

[00:41:30] Angélica Cordero: And the irony is that if you look at labor polls, the war period is the first time ever in American history where married women with children made up the majority or almost a majority of female workers.

[00:41:51] Carys Caffarel: Wow. Talk about a shift.

[00:41:53] Angélica Cordero: So, back to kind of circle back to what we were talking about at the opening of the episode. It just changes everything to me for who Rosie actually exemplifies. I am at a lack of words because she's so magnanimous and encompassing of so many facets of what actually the history of women in the war period were doing, that how do you capture it? And how do you express it? And how do you explain?

[00:42:32] Mary Ellen Page: But I think that's why the posters become so important because that's the one thing that coalesces what everything means, right? You can look at the two, it doesn't matter which one you look at, and it's Rosie the Riveter. And all that that entails. All that that symbolizes. All that that brings to the table. And so you have these two iconic pieces of artwork that actually tell more of a story of today, even than then, because it's become[, …] you hear it all the time. There's podcast called Riveting Rosies that’s about working women. You [brought up] Beyonce. It's timeless, actually. She's timeless.

[00:43:10] Carys Caffarel: Yeah, I actually have, going back a little bit to my impromptu poll I did with my friends. The second question was, “What does a modern Rosie look like?” You touched on Beyonce, so did she. She actually said, “I also think that women in media succeeding, in breaking records are the modern day Rosie. Women like Greta Gerwig, Beyonce, Taylor Swift” She puts in parenthesis “(Cliche, but true) had a huge impact on the world very recently as far as what women can achieve, with Greta having one of the highest grossing movies ever, Beyonce and Taylor Swift having tours and movies that outsell and outperform most male performers. Those three women essentially fueled the economy last year. Just being a woman and existing in a sometimes truly sexist world is something we can do because of the idea of Rosie. Women just being able to own land and have their own bank account, get divorced. All these things happened because those women in World War II stepped up and kicked ass.”

[00:44:17] Mary Ellen Page: When you said modern day Rosie. I think Rosie's always been modern. She's actually the epitome…

[00:44:24] Carys Caffarel: That's a really good point.

[00:44:25] Mary Ellen Page: If you look at the pictures, too, the clothes aren't out of style. People still wear penny loafers. People still wear overalls. People still…

[00:44:32] Carys Caffarel: Denim. Very big.

[00:44:33] Mary Ellen Page: So again, timeless, and I think that's another reason why people are so attracted to the symbolism of Rosie and the artwork because it's a perfect representation.

[00:44:44] Angélica Cordero: This is a subject matter that is very near and dear to my heart. It is incredibly difficult for me to not want to just mind dump the last three, four years of my personal obsession. This is a subject I have spent way too much time researching and thinking about.

[00:45:04] Mary Ellen Page: Oh, I disagree. That's never a wrong thing to spend too much time.

[00:45:09] Angélica Cordero: No, let's be real though. I have several books that I need to continue to read because getting into a better understanding of who Rosie the Riveter really was really helped me better understand the persistent dedication women have given to progress and to our society, in caring for it in a completely different way, where I understood that the war period was just one little step. And you can actually take it backwards from the war and still see women still caring and really showing up the way that we are talking about Rosie now. You can look forward after the war period and you can see those same very Rosies and their children they inspired and their children's children doing similar things. Albeit maybe in different avenues and different arenas, but they're still doing it, right? And so, to your point, Mary, she is very timeless. And while she may have paler skin, as a Mexican Cuban American, I still see her kind of in this nebulous, neutral space because I know who she is. And to me, she means so much more than the depiction of her race.

[00:46:42] Mary Ellen Page: You know, that's really interesting, Angélica, because I never look at her as a White woman. I look at her as a woman. That's the first thing. And actually, I'm going to mention the F word here, feminist. Okay.

[00:46:57] Angélica Cordero: Oh, okay, that F word.

[00:47:00] Mary Ellen Page: Because some people consider that an F word. Okay. Don't get me started on that. But I think […] it's so interesting because people say she's a feminist icon. Other people will say she's not. The interesting thing is that I don't hear the F word used with her very much even though to me, that's exactly what she is. And I was just wondering what your thoughts on that are.

[00:47:24] Angélica Cordero: Carys, do you want to go first?

[00:47:25] Carys Caffarel: Can you just repeat the question real quick? Well, I was so caught up like that conversation between you two. It was so interesting that I just started thinking about the fact that, oh my gosh, I've also never really noticed her as anything other than a woman. She's just this trans-generational icon that seems to sort of mold into… It is almost like a lens of you view her as however you subconsciously want to view her and that, and it works and it just fits. And I think I've never made that realization until you just said it out loud.

[00:48:00] Angélica Cordero: Can I tell you something that is going to blow your mind?

[00:48:03] Carys Caffarel: Do it.

[00:48:04] Angélica Cordero: She actually looks Hispanic to me.

[00:48:07] Mary Ellen Page: Let me, you know…

[00:48:08] Carys Caffarel: I mean.

[00:48:08] Mary Ellen Page: But see..

[00:48:09] Angélica Cordero: I'm serious. I think it's because she looks so Italian American to me. But, I look at her and I see my grandma. [I know] what you're saying. She is who she is to whoever it is that is looking at her and means something to that individual, right? But I know that there are a lot of people who would have liked the representation. Let's just put it out there to say that to have seen more black women doing the same role and showcased, honestly, in recruitment posters would have actually been really nice. And that we didn't get that.

[00:48:50] Mary Ellen Page: And I think that, actually especially talking about the World War II Museum, they're really good about talking about all the experiences. The African American experience, the White, the female, the Hispanic, the Japanese. That I think is one of the brilliant effects of the Rosie artwork that nobody anticipated, which is their timelessness and their adaptability to everyone. I think I've got some updated Rosie artwork that really does celebrate all the, the different women that were working during the war.

[00:49:27] Angélica Cordero: There are so many modern versions of her that are either in a hijab or that are Black women. I have seen so many versions. I wanna say there's probably some parody of Star Wars version of her with like a Princess Leia of some kind. I guarantee it’s out there.

[00:49:48] Mary Ellen Page: I am now looking at my rubber duck. Think about everything that we've been talking about and how she continues to resonate and people attach their own importance to her. Maybe it's somebody that says she got me through high school or something. I guess that's the beauty of it. It's that there's a lot of depth to her spiritual being, I guess.

[00:50:16] Angélica Cordero: Even if, even despite the fact, let's just be real, despite the fact that we didn't see Black American women showcased in a poster in the same fashion, that didn't stop Beyonce from dressing up like her for Halloween, Right? So, obviously, she does transcend race.

[00:50:42] Carys Caffarel: Totally.

[00:50:43] Mary Ellen Page: I think that's really true. Again, I think that highlights what a nerve it hit, the existence of Rosie, that it was something that was really needed. And whether it turned out to be a recruiting poster or propaganda, the point is that she has this image and a message that comes with her image.

[00:51:06] Angélica Cordero: Mhm. You know, one thing we haven't mentioned is that it was decades after the war when Rosie resurfaced and this time it was in the general public. So she was brought front and center to everybody. And that we have ladies of the capital F of the F word that so many people don't like to say to thank for that. I think it's like 30 to 40 years after the war that she kind of just went into the shadows. […] Honestly, let's be real. If she was an internal poster only at a select few factories during the war, can we really honestly even say that she went into seclusion in the shadows? No, I don't necessarily think that's the case. I think she was rediscovered and then appropriately given spotlight, where spotlight should have been given many decades prior.

[00:52:09] Carys Caffarel: Mm-Hmm. .Yeah, I think now just sort of doing a bit of research for this poster, I think it's fair to say that, ultimately, making the Rosie we know today ended up being more of a response to the women stepping up and a way to sort of memorialize their actions and devotion to the country rather than them just answering a call to action. Because, let's be real, jobs were empty. They needed to be done. So, they just stepped up and did it because that's what the country needed to meet this end goal of victory. So I think now, obviously in today's context, she was definitely more of a response rather than a call to action.

[00:52:56] Mary Ellen Page: More of a symbol, trying to put a face to all these women back in the workforce. Right. And, of course, the two pictures depict a much younger Rosie than the average Rosie. But again, I think that people look at it today, at Rosie and say, “We need to finish the work that these women started in the ‘40s.” Equal pay, equal time, equal, universal childcare, that kind of thing. Those are struggles that we still have and continue to flashpoints for women in America. I think Rosie gives them a club to belong to.

[00:53:35] Angélica Cordero: And I think the other thing, to that point, is so many people look at the fight for women's rights through a very specific and narrow lens that is irrespective of the things that we're just talking about. The reality is that the fight is all encompassing of all these issues. They go hand-in-hand with one another. When you start really actually slicing everything and understanding [that] all of these things work in conjunction with one another, they work in concert together, then you start to really understanding the real depth of it all. I think maybe that's why I love her so much. It’s that she has now become something so much bigger than what she was when I was growing up. Which is crazy because she was so big for me growing up, and the fact that she's so much bigger now is mind boggling.

[00:54:41] Carys Caffarel: Yeah. That just speaks to the true testament of what she is. The fact that she's able to morph and grow and continue to be relevant.

[00:54:50] Mary Ellen Page: And remember, the three of us met…when we put our group together with three other women, the first thing we called ourselves was the Rosies. It wasn't even, it just happened. It was exactly the way we felt. The Rosie poster doesn't depict women going to school and yet we felt like Rosies doing what we were doing. And I think that's what is so incredible about how she has evolved. It's that it's not just women working. it's women's empowerment. It's women's approach to the world. And it's not just holding a rivet gun, making sure that your aircraft carrier doesn't sink. When it started, it could never have anticipated what it has become.

[00:55:33] Carys Caffarel: Yeah. 'cause I mean, ultimately she's a symbol of, “Hey, it's okay if you wanna better yourself. It's okay if you wanna aim for more. It's okay if you wanna shatter the glass ceiling, go back to school. Do whatever you want. It's okay. it's good. You should go for it.”

[00:55:49] Mary Ellen Page: And you don't have to wear a dress to do it.

[00:55:56] Angélica Cordero: Yeah.

Carys Caffarel: Exactly! Pants and flats!

Angélica Cordero: And penny loafers!

[00:55:59] Mary Ellen Page: This is a good time to wrap it up today, ladies. This was great. I love talking about Rosie. We were talking before we started recording that maybe we need to do another show and I think that there's still a lot of material that we could do with another show. So any of you out there who have any questions about Rosies, just give us question and we'll try to answer it for you. But, I think that we've actually covered quite a bit of territory here.

[00:56:27] Angélica Cordero: Yeah.

[00:56:28] Carys Caffarel: A lot. Yeah.

[00:56:29] Angélica Cordero: Well, we have some amazing and exciting news to share with our wonderful listeners who we love very much. Arizona State University News has featured us on their website and has captured our lovely friendship. We'll make sure to include the link in the transcript in the show notes. So that you can also read it as well.

[00:56:53] Mary Ellen Page: Thank you, Carys. You darn well better be back on the next episode because it's been way too much fun being with you two this last hour. It's just been phenomenal.

[00:57:02] Carys Caffarel: It really has. I mean, this hour has just flown. Like you said, I could talk all night. So guys, make sure that you connect with us. You can follow us on Instagram at WorldWarShe. Or you can subscribe to our newsletter on Substack at worldwarshe dot substack dot com.

If you have a topic you want us to get into, shoot us an email at worldwarshepodcast at gmail dot com.

[00:57:29] Mary Ellen Page: And to all of you, we'll see you again when we get our next set of orders.

[00:57:34] Carys Caffarel: Yes, ma'am.

[00:57:35] Angélica Cordero: Over and out!

Share this post