This episode of the World War S.H.E. podcast features a compelling conversation with guest Kaye Ackerman, hosted by Laura Bailey and Angélica Cordero. Ackerman delves into her father's experiences in World War II, tracing his steps through the European Theater of Operations and discussing her own journey in piecing together her father's wartime history. Through extensive research and personal stories, the episode illuminates forgotten aspects of World War II, highlighting how the war impacted soldiers and their families. It showcases how Ackerman's research not only brought her closer to understanding her father's experiences but also helped others connect with the histories of American soldiers who fought for the liberation of Western Europe. The episode underscores the importance of memorializing and understanding the human experiences behind historical events, exemplifying dedication and passion for preserving the legacy of those who served in World War II.

This episode was recorded February 2, 2024. Transcript included below.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Angélica Cordero: Hi, and welcome to World War She, a podcast that shares the human experiences and the forgotten aspects of World War II that rocked the world then and echo today. I'm Angelica Cordero, and today I'm here with Laura Bailey and a wonderful guest. Tell us a little bit about our guest today, Laura.

[00:00:20] Laura Bailey: Hi, Angélica. It's great to be back again. And yes, I am extremely excited to introduce to everyone my guest today. Her name is Kaye Ackermann. Just to give you a little personal background for myself where I've come to know Koi.

When I started my World War II journey, I've always had an interest in it, but when I started my World War II journey and started pursuing the degree, I quickly found out that I was not alone in my world of interest. For most of my life, I felt isolated because few people wanted to talk about the war. But once I started getting out there and getting involved, I started finding more and more people that shared the same interest, the same passion, just different tracks, if you will, of interest. And through the course of research and being introduced to a World War II veteran, our paths crossed and I'm excited for you to hear exactly how that happened.

Kaye Ackermann lives in Charlotte, North Carolina now and she began searching for information about her father's experiences in World War II over 30 years ago. And for more than 20 years, she pieced together all the bits of information that she could until she was certain that she knew where her father had fought every day that he was in the European Theater of Operations, also known as the ETO. Since then, she's made two trips to Europe to trace his steps and the battles.

Kaye was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky. And as a graduate of Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, she recently retired from a long career in international finance. As I mentioned, she now lives in Charlotte and spends most of her free time rescuing dogs and providing free research services to assist the European citizens who worked to memorialize the American soldiers who gave their lives for the liberation of Western Europe.

So, if I may, Kaye, hello, how are you today?

[00:02:15] Kaye Ackermann: I am fabulous. Thank you for having me.

[00:02:17] Laura Bailey: Absolutely.

[00:02:19] Angélica Cordero: We’re so excited to have you.

[00:02:21] Kaye Ackermann: Thank you, Angélica.

[00:02:22] Angélica Cordero: We had the pleasure of meeting, was it last year? And we went out to Fredericksburg here in Texas where the National Pacific War Museum is at.

[00:02:33] Laura Bailey: That is correct.

[00:02:34] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, it was a good time.

[00:02:35] Laura Bailey: It was a great time. I'll start with just a little bit of history. And Kaye, if you will help me as I go along.

Kaye and I met through a World War II veteran by the name of Vern Schmitt, who is 98 years old and lives in Fresno, California. He served with the 90th Infantry Division in the European Theater. And, as it turns out, through our independent research, we found out that my grandfather served with Vern in the 90th. And Kaye's father was in the 712th Tank Battalion that was attached to the 90th. So, we are fairly certain that Vern, my grandfather, and her dad were together at various points of the war in 1945. So, it's been a thrill.

[00:03:22] Angélica Cordero: That is so wild.

[00:03:24] Laura Bailey: It's been a thrill, but I don't want to get too far ahead. The first time I met Kaye in person, she amazed me with her knowledge and our conversation, with my mother was with us, over the course of three or four hours. That first meeting was a constant state of cold chills, revelations, coincidences, et cetera. And I really became, I'm going to be honest, enamored with her because of her intelligence as a woman. Number one, she's a very strong woman, but number two, just the vastness of knowledge that she had about the war. I won't call them the tricks but the things that she had learned about researching and how to find details that most people would think were long forgotten.

After that day, she says I get her in trouble a lot because we end up in random places across the United States. And it's been fun, but if I may, I want to turn the clock back just a little bit. And Kaye, I think the best way to start is just you talking about your dad. Tell us a little bit about him and when you first realized he was a veteran of the Second World War.

[00:04:28] Kaye Ackermann: My dad was Sergeant Roland Ackermann. He was from Cleveland, Ohio, as opposed to Louisville where I was born. And he was drafted in March of ‘42. Did his basic training, I believe at Camp Perry, but then he was transferred to Fort Knox which is just south of Louisville. And in Fort Knox, they had set up the AFRTC, which is the Armored Force Reinforcement Training Center. So, in other words, he was being trained to be a tanker, and he was there for two years.

My parents is a very typical meeting story of that time frame, because all the GIs would go into Louisville on the weekends. The USO would have these big dances at the YMCA. My mother was the oldest of seven girls in her family. So, she would grab up all of her younger sisters, and I think they got on the streetcar. I'm not sure how they got down there. And go to the YMCA. And that's how she and dad met. They were fantastic dancers. Then after the war, when he came home, he decided that he did not want to go home to Cleveland. He wanted to go home to Louisville. And he got to my mother's parents’ house at probably, I think it was about 1:30 in the morning. The entire house got up. He asked her to marry him that night. And they were married nine days later, which is a very typical story for a lot of these GIs.

I wondered, I never asked what time of the day they got married. It turned out they got married at eight o'clock on a Saturday night, which I thought was very odd. And then I realized that's probably the time slot that the church was available because, again, everybody was getting married. You had to get married at a church that was probably within walking distance of your home because there were no cars at that point.

So, from there they rented an apartment across the street from my grandparents. I'm sure my dad was just delighted with that. [They] set up their lives in Louisville together. Dad was, of course, not from Louisville. My parents were very typical children from the Depression, both being…my father was the oldest child in his family. My mother was the oldest girl. So, both of them had to drop out of high school to help their families, but they made a life regardless. I don't think they ever considered going back to high school or anything just because they were already in their late 20s and they wanted to move on. [They] bought a home and my sister and I were born. We had an idyllic childhood, but there was always another being in the house. I remember thinking that from the time I was about five years old, that the war lived in the house with us. We didn't talk about it, but that's the way things were. That is not atypical for somebody from my generation.

[00:07:12] Angélica Cordero: When you say that, what do you mean by that? Can you give us a little bit of some context on what was it in that made the house feel like that?

[00:07:22] Kaye Ackermann: I don't think that there are many World War II veterans, and particularly in that time frame when it was so fresh, late 40s, 50s, 60s, that ever really relaxed. I know that if we were, let's say we were at a high school football game and my dad was waiting for my friends and me to get done with our socializing and go get in the car. He was still always looking around. It was just a part of his being growing up. My father was a big man. His nickname in high school was Tarzan and his reactions were sometimes faster than his thought process. And I think that was just a matter of training followed by experience, and the experience wasn't good.

[00:08:11] Laura Bailey: He was always on alert. Yeah.

[00:08:13] Kaye Ackermann: Yes, that's it. He was always on alert.

[00:08:16] Angélica Cordero: That must have been a significant influence on you as a child growing up, if you could sense that.

[00:08:23] Kaye Ackermann: I could sense it, but even so, I just kind of accepted it as part of dad. I didn't understand why it was. It was just part of dad, but he was a phenomenal father, which is what really amazes me. Like, how did he do that? And my sister and I will both say he was perfect. He was just the perfect father. He was very involved in anything we were doing.

My sister and I are very different. We had different interests. I'm the serious studious one. And my sister, I don't know, was concerned about her hair and what it looked like. And you've met me. So you know that that's not a big concern for me. On the few things that were ever said about the war, he didn't say them to her. He said them to me even though I was quite a bit younger. So, I think again, that this is something that happened in a lot of people's houses and I think people from outside our environment did not have the appreciation for dad that we did.

[00:09:25] Angélica Cordero: You're mentioning something that for me, just growing up next door to my grandfather who served in the war, I don't know that I ever saw him be the same way necessarily. Granted, I didn't have necessarily that same context growing up, but I know that in hindsight, if I think about growing up next door to him, a lot of what I think about is how did he do it? How did he almost swallow the sentiment that you just described from your dad, on a daily and still somehow smile and crack jokes and be so loving?

[00:10:05] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah.

[00:10:06] Angélica Cordero: I'm with you. I don't understand how they did it either.

[00:10:10] Kaye Ackermann: There were some things that happened Like my sister told me about this that when M.A.S.H. came out. It was a movie first. By that time, she was dating her husband to be. So, mom and dad and Debbie and her husband or boyfriend went to the cinema, because that's what it was called, and they went to see M.A.S.H. About ten minutes in, Dad got up and walked out and sat in the lobby. I don't know whether mom went out and joined him. I suspect she did, but my sister and her boyfriend stayed and watched the movie. When she came out and asked mom, “What was that about?” And she said, “Well, you have to understand. Your father doesn't think anything about war is funny.”

[00:10:57] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, you know, I had a similar experience with my grandfather when Saving Private Ryan came out. That whole opening scene is them storming the beaches of Normandy. And I remember just how choked up he got at that whole entire scene. It is interesting to be on the outside of looking in on their experience in the aftermath.

[00:11:25] Kaye Ackermann: The big movie when I was young The Longest Day, which is also about D-Day. And I remember, I don't know why my parents let me do this. I was like six or seven and my best friend lived next door and her parents were going. They said, “Do you want to take Kaye?” She said, “Yeah.” So I went with them and I watched that movie. I have no idea whether I thought it was true. I have no idea, but I reflect on that and think, why in the world did my parents let me go see that? And then the second part of what I think is, I wonder what dad was thinking. I don't believe he ever asked me any questions about it. You know, “Well, what'd you think of the Kaye?” I don't think anything like that happened. And just for the first time, I could never watch it. And I watched it again, probably six months ago, the first time in over sixty years.

[00:12:19] Angélica Cordero: Wow.

[00:12:21] Kaye Ackermann: And it's pretty rough. It really is pretty rough. Some of it's comical, you know, as always, but it's pretty rough.

[00:12:29] Laura Bailey: I never knew your dad, Kaye, but perhaps he allowed you to see it because he wanted you to know and he couldn't find a way to tell you himself.

[00:12:39] Kaye Ackermann: That's quite possible.

[00:12:40] Angélica Cordero: The other thing that it, that what you just said brings to mind to me is…so during the war, there was a woman who was an anthropologist. Her name was Margaret Mead. And one of the things that she was evangelizing, for lack of a better word, was that Americans shouldn't protect their kids from the atrocities of war, from seeing the news and the newsreels and so forth. She said that they needed to actually be exposed to it. The article is really great, but it makes me think that of you at six. And it almost seems now in a modern context ludicrous to think that any parent may do that, but it’s interesting to consider what Laura said that he didn't have words and maybe the movie would help.

[00:13:37] Laura Bailey: You know, Kaye also, just through conversations she and I've had and just the time I've had with her during our friendship, she, I'm sure at that age, she was wise beyond her years. I mean, she just has a wisdom that I think came with her at birth and I do not say that lightly. I could see that. I definitely could.

One point I'd like to make, if I could go back a couple of comments. You were talking about your grandfather and how they could crack jokes and remain strong and CO's father as well being on alert at these football games. The thought that crossed my mind was [that] they were still serving and protecting, not in a wartime, but they were serving and protecting their families. And so, they were keeping the stiff upper lip and they were shoving things down inside until perhaps they were alone. But, for the most part, when they were living out their days, they were still in that protective and defending mode. I mean, that's my opinion.

[00:14:46] Kaye Ackermann: I think that's very true.

[00:14:47] Laura Bailey: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:14:49] Angélica Cordero: I was just going to say that I think what you just said actually is so imperative to even thinking about veterans now who come back and that they too are also likely in that same mindset. Despite the fact that we're talking about now it's, war is war and whatever it is that they see is so imperative. Intense and not, not anything I think that any of us really have context about who haven't served. That what you're saying, I think, is so spot on. It makes the most sense.

[00:15:22] Laura Bailey: The difference I feel today versus then, that generation was not very expressive. They did not tell their feelings. My grandparents, you know, who I adore still, they weren't ones to tell you they loved you. They showed you, which I prefer, personally, but it's hard to wrap your mind around. People didn't talk about post-traumatic stress disorder, although that wasn't its name then. They didn't talk about that then. They suffered with it alone. They were prisoners to it in many ways. And, I believe, and Kaye can share, I believe her father in his own way struggled with it. And I will use that to lead into my next question with Kaye. When did you realize that extra being in your house was the war? Was there a moment? Was it a natural progression? Was it a conversation?

[00:16:17] Kaye Ackermann: It was reflection as an adult.

[00:16:19] Laura Bailey: Okay.

[00:16:20] Kaye Ackermann: So it's not something that I put a name on at the time. But looking back, it's just like when I was growing up, the way mom and dad's schedules were, dad would always cook dinner. Our kitchen was small. More than once, if dad went to pick up like a hot pot off the stove and then take it across the counter and put it in the sink, he would tell us to move because he had this pot of boiling water or whatever it was. Something that might've taken any of us like two hands to pick up, but with him it didn't. And I remember more than once he would just like say, “Kaye, move out of the way.” and he would just go to move me, but it would be much more forceful than was necessary or intended. It was just “Danger! Danger! Kaye, get out of the way!” And he was just reactive.

Angélica, something that you said about, was this discussed as an adult? I came to know and by adult, I mean I was close to 40 when I found out, when my mother revealed a few things. And, that's when I realized that there were times when dad was going through difficult times and I guess they probably went in their bedroom and sat on the edge of the bed so he could talk about it because except for a couple of limited times that I'll share with you, didn't certainly didn't happen in front of us except two times.

Didn't happen to my sister. I don't know why, again, it could be because I'm a lot more serious than she is. There was one time, when I was about nine. It was in the summer. It's really hot in Louisville in the summer. It's very humid and dad was out cutting the grass. Of course, I had to be with him because I was always with dad. I was sitting on the back porch and he got done cutting the grass. I went in to make him some iced tea, went back out. We were sitting on the steps next to each other and he made this gesture. I remember that he took his right hand and put it on the outside of his right leg like at calf level and then rubbed his hand up past his knee and up the side of his leg a bit. And when he did that, he said, “You know, when I was wounded in the war, they thought they were going to have to amputate both my legs.”

[00:18:44] Angélica Cordero: Holy crap.

[00:18:45] Kaye Ackermann: Well, this is a bit much. But again, I was nine. He apparently thought I was ready to take this. I had no idea what he was thinking, but he wasn't in a despondent way at all.

It was just kind of conversational. I kind of looked at him. I'm sure my eyes were big as saucers and he said, “Now, your mother doesn't want me to talk to you girls about this.” And I said, “Well, then I don't think you better talk about it, dad.” And it was never brought up again.

Gosh, I was probably in late teens or in my twenties, I remember hearing a Vietnam veteran talking about getting in a hot bath of water running his hand up his leg and having shrapnel come out. And so, it took me probably decades before those two little comments connected in my head and I realized that's probably what was happening when dad did that. He was pulling shrapnel out of his legs.

Now I have his official military personnel file, the OMPF. Those are the files that burned in the 1973 fire in the archives in St. Louis, but my father’s survived somehow. And I'm the only person I know who has their soldier’s OMPF.

When I went looking through it, the first thing I found was that his wounds that were suffered in Germany, in February of 1945, were shrapnel and concussion. I thought, “Wow, that fits together for the first time,” but that was an isolated thing. For years, nothing happened again. Then, fast forward to, gosh, 1969, May of 1969, I came home from school one day. I was in ninth grade, and when I walked in the house, everything was wrong. Everything about the whole picture was wrong.

First of all, mother was home and she shouldn't have been home at that hour. Dad was sitting in the dining room sideways on one of the dining room chairs. And he had his head down and everything, and he was kind of sunken. So I said, “Dad, what's mom doing home?” And he looked up at me and he said, and this is a quote, he said, “You know, the largest mass grave I ever saw had about 250 bodies.”

Whoa. I'm in over my head now. And I just looked at him and he kind of went, you know, like he expected me to answer. And I thought, I just don't even know how to handle this. I don't know who mom was talking to on the phone. This was back when the phone was stuck to the wall. I suspect it was probably my dad's doctor or something. But anyway, she got off the phone right away, grabbed dad, ran down the hallway and they went in their bedroom and I was still just standing there. I mean, I had my books in my arms and my purse over my shoulder and the dog was dancing around. And I just went upstairs. I went up to my room and, later on, about two hours later, mom came to the bottom of the steps and said, “Colleen, your father and I are going out to dinner, would you like to go?” And I said, “Oh, no. You all go out and have a good time, I'll just stay here.”

It was never ever mentioned again, ever. Even though dad died two years later, mom never thought to explain it, and I didn't think she'd tell me so I didn't ask her. But I did find the answer.

[00:21:59] Angélica Cordero: I was just about to ask if you knew what it was that he was making reference to.

[00:22:04] Kaye Ackermann: I did, but it…it was a long time. And by a long time, I mean, when did I call you all excited that I'd found it, Laura? About three months ago, maybe?

[00:22:14] Laura Bailey: Yes.

[00:22:15] Kaye Ackermann: And I have for years, I've kept a lookout for the mass grave that they would have seen. I'd kind of ruled out [that] it could have been at Normandy. But I didn't think it would have been, but there was a lot of potential in the Bulge.

What I couldn't figure out in the Bulge is that the ground was frozen, extremely frozen in the Bulge. So, how would they have dug a hole that was big enough for that? When I did my first tour of dad's battles, I did it on exactly the 75th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. So, this was in 2019 and my guide told me at one point, “There was a big mass grave back there, but we can't get to it today, but there was only 160 bodies.” And I said, “I don't think he really counted them.” And so we didn't talk about it anymore, but I just kept trying to research it and contact people in Luxembourg [to] find out around Bastogne and Luxembourg if anybody knew about it. And I didn't, for some reason, nobody did at that point.

Just recently, on a World War II Facebook page, somebody posted about it. And when they did, it caused me to go to what is now a website. I've looked for a website before. I found the website and there were 160 Germans, but there were also Americans in the same grave. And in trying to [research it] again, to figure out how in the world would you dig a hole big enough, it turns out that it was a bomb crater. So temporarily, because you have to keep them away from animals and you have to keep them away from other things, but you have to protect the bodies as much as you can. And they used a bomb crater.

[00:24:02] Laura Bailey: This wasn't the Battle of Oberwampach, correct?

[00:24:05] Kaye Ackermann: No, it was just before it.

[00:24:07] Laura Bailey: Just before it. Okay.

[00:24:09] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah, this grave is just over the line about, gosh, a mile and a half outside of Bastogne, Luxembourg.

[00:24:19] Laura Bailey: Okay.

[00:24:20] Kaye Ackermann: Oberwampach.

[00:24:21] Laura Bailey: Okay. If you don't mind, will you give a brief scenario of Oberwampach? Because you and I've had many discussions about it, but I would like our listeners to learn about it because it was a very fierce battle and is rarely heard of. I think it adds a lot of context to what your dad was reliving after the war.

[00:24:44] Kaye Ackermann: One of the last things that my mother told me before she was going into dementia was that dad had fought in the Battle of the Bulge. She told me this in ‘93. I didn't know that he had or hadn't. I just hadn't thought about it. Cause we couldn't talk about it. And then, she happened to say to me one day, “Well, he never referred to it as the Bulge. He referred to it as the name of the town where they had a really big battle.” And I said, “Bastogne?” No, that wasn't it. I was naming everything I knew to name. But I didn't know anything about a little town called Oberwampach.

Eventually I came to be friends with a man named Aaron Elson, who has written a number of books about the 712. His father and my father were both in Company A and probably fought many battles together. So Aaron, years ago, started going to the 712's reunions. He is actually a newspaper editor. He started taking his recording device, way back and recording these interviews and all these guys talking. It's just a wealth of information. I'm really blessed to have access to that.

So one time all of a sudden it hit me that Aaron was the person I was supposed to be asking where was this battle? And I remember it was late at night and I was, we were messaging on Facebook and I just went back with one question “Where was the worst battle that the 712th had in the bulge?” And he came back with one word and it was Oberwampach. And all my mother could remember was that it was a funny name. And I thought, “I finally know this. You know, after all these years, I finally figured it out.”

So Oberwampach is in, kind of northern Luxembourg. Luxembourg's a really small country. It's not very far from Bastogne. But after Germans had really lost control of Bastogne, well, perhaps never had control of Bastogne. This was going to be a stronghold that they were trying to take. And they went to this little town. The population then was only about 250. We went in and, fortunately the tankers sat in the Southwestern corner, which gave them a great vantage point to see when the Germans were coming.

It was about 300 Americans against 900 Germans and the 900 Germans were the SS. These were the men who had the same blood type so that they could be transfused on the field if they had to be. And they fought for 72 hours off and on. It was actually nine battles in 72 hours. Snowed like crazy. Most of the time, seven of the battles were in darkness. This was January 16th, 17th, 18th…17th, 19th. Yeah. Those three days. In the end, [the Germans] lost hundreds. It was snowing so hard they couldn't get a body count. And we lost three. So against all odds, we did what we had to do.

[00:27:50] Angélica Cordero: Three in his company? Is that what you're saying?

[00:27:53] Kaye Ackermann: We only lost three in the entire 90th Infantry Division

[00:27:57] Angélica Cordero: That is wild. And, just So evident about how hard they were fighting. For people who don't know, the Battle of the Bulge was one of the, if not the largest, battle fought on the Western Front in Europe in World War II.

[00:28:12] Kaye Ackermann: We had 100,000 casualties, and close to 19,000 deaths in a period of five weeks.

[00:28:29] Laura Bailey: I was just going to say we had 16 million people deployed or signed up for active duty during the war. And as I mentioned earlier, I don't mean to get off-topic by saying this, but it's important for me to just state it. Kaye and I have found out through our research that my grandfather was present as well those three days. It's just mind-boggling to me how small the world has become, how small the war has become through our conversations and our research, and that we both had these men come home and have such a huge impact on our lives with that history inside them.

[00:29:15] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah. When I talk about... I mean, I remember talking to my godmother, gosh, in the late nineties about my dad and his history of heart attacks when I was growing up. He had his first one when I was eight and then there were several more before he died when I was 17. Then there was all the regular issues—cholesterol and high blood pressure and stuff like that. And they didn't have as many meds back then. They didn't have meds that were as good as what we have now. And that would have certainly affected everything. But I remember when my godmother said, "Oh Kaye, the war killed your father." And I said, "Well, we've always suspected that, but nobody would ever tell us as the children. They just wanted us to have a good childhood." But it's true that the war did kill him.

[00:30:02] Laura Bailey: And, you know, like I said, I never knew him, but the more I talk to you and get to know you, I honestly believe that. And one story you've shared with me that I would love for you to share today, if you don't mind, that adds... not that credibility is necessary, but it adds to the certainty that the war killed him. Um, will you please share about when you looked for his medals from the war?

[00:30:26] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah. When my father died, his parents were both still alive. So, my father was raised Catholic. In his... there was an old jewelry box sitting on my parents' dresser. It was kind of one of those things, you just... it was forbidden fruit. You weren't supposed to go in there, but we always peeked in it. And I remember one day looking in there, many times looking in there. It wasn't once, and there was the remains of his crucifix, his rosary, which he had carried with him to the war. So it was just like, the crucifix itself and some beads on either side of the crucifix. But there were also some war medals there.

I know there was a bronze star. I've held it in my hand. I would have had no reason to know what a bronze star looked like as a child otherwise. So, when Dad died, his mother asked us to have him buried with his rosary. We said, "Oh, sure. Okay." We went in the jewelry box, and it was all gone. We don't know where it went. We know that neither my mother nor my sister nor I did anything with it. But I suspect, because Louisville's on the Ohio River, if you want to get rid of something, you drive over the JFK Bridge, you pull over in the passenger lane, and you throw it off the bridge. And I suspect that's where it is.

I think one day, and my guess would be that it was after the day that he told me about the mass grave. I suspect it was sometime after that that he just said, "I've got to let it go." And he threw them out. I can't prove that, but he had to do something with them, with himself. And he had to do it willfully.

[00:32:01] Laura Bailey: So, Kaye, his journey and your life and your research to try to fill in the gaps has been truly a jigsaw puzzle for you your whole life. The things you were living in real-time, you're finding the answers to now. And you know, if yours is anything like mine, you're still missing several pieces. But one thing that's been very inspiring as I've gotten to know you is that you've used your own history and your own experience and research to help other people, specifically in Europe, to find their own answers. Do you have a favorite story that you could share with us of how you have helped someone or more?

[00:32:47] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah, I probably do. You know, I've worked a lot on... and I don't know how many people who will listen to this podcast are aware of this, but many, I would dare say most, of the American soldiers' graves in Europe are adopted by local families. A family adopts Joe Smith's grave. Then, that family passes that grave down in their generations.

So, I started just a few times when I found people that were looking for help. And they would come to the 90th Infantry Division page, for instance. Become a member, and they would say, "I'm really looking for information on this soldier, but I can't find it. I want to get in touch with his family in the U.S. I've adopted his grave." Recently, I had a young man from Belgium who adopted a grave in Margraten Cemetery, which is tremendously organized in its adoption process. They have a whole website and everything. And he said, "You know, I just can't get any information on this young man." I reached out to him and I said, "Let me see what I can do."

They always want the same thing. They want a little bit of history. They would like to get in touch with the family and let the family know that that soldier's grave is being decorated on his birthday, on his death date, things like that. And they always want a picture. The hardest soldiers to find are the ones that are only children because there's no sideways growth to the family tree. And so you can't call that soldier's brother or sister and say, "Hey, you got a picture of your brother?" And say, "Somebody's taking care of his grave" because they're always delighted to hear about it.

Just recently, and it took me a year and a half, to find this one, but I was determined to get it. We had a medic in the 90th Infantry Division in the 357th Regiment who did not die in combat. He was murdered. I pulled a copy of his individual deceased personnel file. And he was killed by a bullet to the head. I found his family, and they had pictures.

It took a while to find them. And I mean, it was like this timing thing that was like something out of the twilight zone. This woman was just cleaning and getting ready to go through boxes and get rid of stuff. She had these pictures she was going to send to her nephew because he was really interested in the war. And she found the one you always want, the picture in the uniform. That's the one you always want. And so sure enough, I mean, of course, she was stunned.

And as usual, she then went and told her friends about it. When she went to tell her friends about it, they said, "Oh, no, that's a scam. Don't talk to that woman. Don't you know," and I had to convince her that I was really... I sent her my whole bio saying, "No, I'm really legitimate. I really am."

But to send that picture to that young man, hear the excitement in his voice was just phenomenal because finally he knew what his soldier looked like. And even at Christmas, he wrote me another note and said, "I just want to tell you that you gave me my highlights this year."

[00:36:02] Angélica Cordero: That's so sweet. That's so sweet.

[00:36:05] Kaye Ackermann: That's when it matters.

[00:36:07] Laura Bailey: Yeah, it does.

[00:36:08] Kaye Ackermann: The one you always want to find, and this is what I would say, I did some research on a documentary that was made about an airplane crash on Christmas day during the Bulge in Belgium. And it happened to have happened about an hour and a half from where I stay, at a bed and breakfast there.

They were working on it. I was with a whole group of people that happened to be working on it. And I said, “Well, you know, what can I do? How can I help? What can I do from state side?” And they said, “We were trying to find the families of all nine people, all nine men on the plane, but we got three men we just can't find.” And there was this one we just ran into dead ends on all the time. And it took me forever. Oh, it took me, I think 250, 300 hours, but then I suddenly hit the jackpot, twice.

First of all, we managed to get the ID PF, the personnel file that the archives kept saying was lost, but we finally managed to get it. And then that allowed me to put together the family tree properly, even though I really figured that I knew who his parents were, but I couldn't prove it. And one thing led to another, and my phone rang after I'd connected with the family. My phone rang and I didn't recognize the number.

So, I just answered the phone and said, “Who's calling please?” And this man said, is this Ms. Ackermann? I said, “Yes, it is.” And he said, “Ms. Ackermann, this is Eddie O'Rourke.” Well, that's the same name as the co-pilot on the plane that I had worked so hard to find. And I said, “So, what relation are you to First Lieutenant O'Rourke?” And he said, “I'm his cousin. And my cousin Hugh just called me to tell me what you all are doing, and I can't believe what you're doing on the plane crash.” And I said, “You know about the plane crash?” Because he would have only been about three years old when the plane crashed. And he said, “I know all about it. I've got the file. I've got his medals.”

And then he said, “I've even got the wings that he was wearing on his lapel when the plane crashed. They're bent in half, but I have them. It's all up there with a picture of him that ran in the newspaper when he died, and they're in a shadow box in my man cave.” And I thought, “Holy cow, how did that happen?”

So when we premiered, we had our own little premiere for everybody. This was with Footsteps Researchers and Joey van Meesen, Bob Konings, who runs the Bed and Breakfast in Belgium. We all flew over to Belgium to watch the release of the documentary. It's called Ghost Plane of La Fosse. It's on YouTube. We gave it to the world as a Christmas present on Christmas Eve the year it was done because again, the crash itself was on Christmas Day. We all went over there together, and Eddie flew over to meet us. I met him at the airport in Brussels. So, some really cool things that have happened. None of which I would have ever thought.

[00:38:56] Angélica Cordero: That's so wild and so amazing. I know that, if a lot of people that are listening don't necessarily know, it's like what Kaye was saying earlier that a large majority of the records for it was, was it just army that was affected in the seventies of the fire at the National Archives?

[00:39:21] Kaye Ackermann: Well, 85 percent of the records were the Army and then the Air Force was part of the Army during World War II. We didn't have a separate Air Force until 1947

[00:39:29] Angélica Cordero: Right.

[00:39:31] Kaye Ackermann: Navy and Marines were offsite.

[00:39:33] Angélica Cordero: Wow. Yeah, it's, it's, I can, having my, done my own work to try to locate information on my grandfather, I can empathize with how amazing, it was to have that connection just kind of come out of nowhere. But then also to have everything that he had is just such a treasure trove when you're trying to piece together everything.

[00:40:00] Kaye Ackermann: Well, you know, and it took us so long, I mean, multiple people had worked on it. It was just, the file was lost. Now we know that when Eddie checked out the file, wrote to the archives in the early 90s to get a copy of the file. They took it out, made a copy, sent it to him. And then when they went to put the file back, they put it in the wrong place. So, that's why we were not able to locate this. We just had nothing on him. And then, to think that he called me and I kept thinking, “We have 330 million people in this country. The one I've been looking just called my number.”

[00:40:31] Angélica Cordero: Mm hmm.

[00:40:32] Kaye Ackermann: That's phenomenal. I still keep in touch with him. We're Facebook friends. I still keep in touch with him, and I'd love to make a trip to New York to visit him cause he's getting up there. He's about 86 now.

[00:40:49] Angélica Cordero: Do you now spend a majority of your time working on making these kinds of connections for people in general or for more specifically the cemeteries that you were talking about?

[00:41:02] Kaye Ackermann: Sometimes I do it for, if I run into something, and specifically on Facebook, is where you would see this sort of conversation most often. And so I do go, and usually I volunteer on it. I just reach out and say, I think I can help you. But I also have started, doing a little bit of public speaking and like I do a presentation called finding your soldier. And how to find your soldier and put together and some of my best stuff I found one day because I switched search engines. I went from Google to Bing. Bing had actually one of the pictures that I sent you, the one of my father standing in front of the tank, pointing at the hole. For some reason, it had not broken into the Google world yet. It was I switched to Bing. And then once I posted it, it was all over Google. It was bizarre.

[00:41:52] Angélica Cordero: That is wild and weird.

[00:41:54] Laura Bailey: Kaye, I have two stories of yours that are coming to mind. I'm trying to decide which one I want you to tell, maybe both. But could you share first about the funeral that you were able to recently attend?

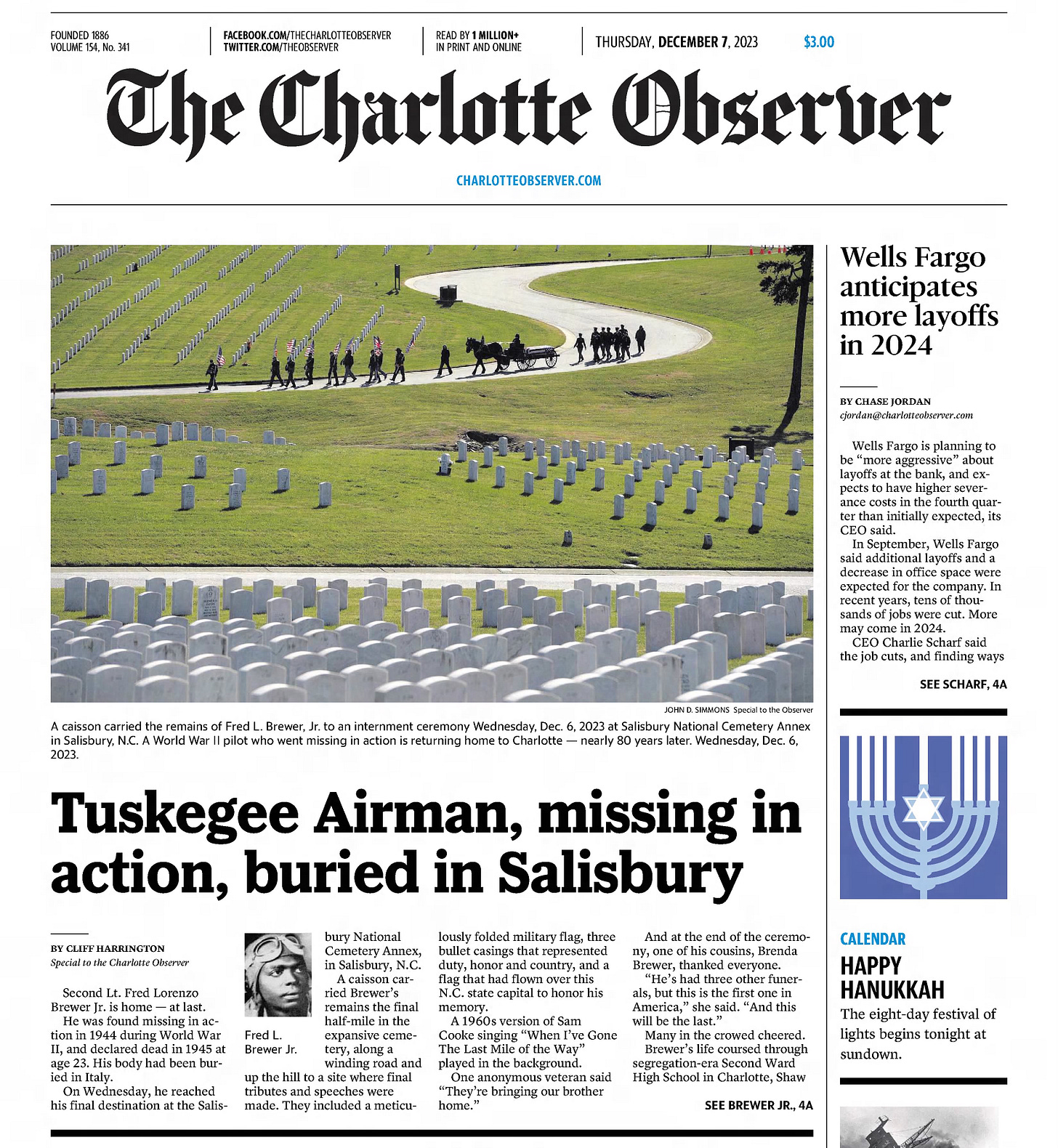

[00:42:06] Kaye Ackermann: Oh, gosh. Oh, gosh. That was something else. We had a Tuskegee airman from Charlotte who was killed in October of ‘44 when his plane went down over Germany and his body was never recovered. As it turns out, his plane went down and then, somebody found it and he was buried. I want to say he was buried in a church cemetery or something at first.

Then he ended up being moved to a military cemetery of the United States in Northern Italy, but he was an unknown soldier. And then eventually, they realized that they thought they could get some DNA off of it because one of the things that went down near him was his goggles. And they thought they could get DNA off the goggles. Anyway, so they got the DNA.

They hooked up with a genealogist that I got to meet at the funeral. And she tracked down a niece and nephew. So, here we are all these years later, bringing this man home finally.

So my cousin and I, she's a genealogist, we decided, “We're going, that's it. We got to go.” We went up to the national cemetery up in Salisbury, North Carolina the day he was being buried. Except for those two family members, nobody else there knew this man, but probably a couple hundred people showed up. And it was pretty phenomenal. An F-15 flew over as we were standing there, which was pretty phenomenal, but then there was a really elderly man standing there. And I thought, “Boy, he's really old. What's with him?” And I noticed that the news was interviewing him. So, I kind of stepped just to the side to hear what they were asking him.

And as it turns out, when the Tuskegee Airmen was in the air, he was playing defense to protect our airplanes from another group that were playing offense. And this man believes that the man that the Tuskegee Airmen that we were burying is the one that shot down the plane that was going after him. And it was this man's 101st birthday. And he said, “The thing I want to do today,” he lives in Statesville, North Carolina, which is just about an hour north of Charlotte. And the thing he wanted to do on his 101st birthday was go to this funeral for this man. So now they're going back through the reports to figure out if there any way they can put together whether or not it was his plane that shot down the one that was going after this 101 year old.

[00:44:36] Angélica Cordero: Can you imagine if they are able to make those connections?

[00:44:41] Kaye Ackermann: It would be a great movie.

[00:44:42] Angélica Cordero: It would be a great movie. Wow, that's so just wild and crazy. Did he mention how it was that he found out or had put two and two together to even be there that day?

[00:44:56] Kaye Ackermann: He didn't at that time. I really want to get somebody who does a lot of interviews…Laura and I have encountered a number of people in our research who do a whole lot of interviews of World War II vets anytime they get the opportunity. And I'd love for somebody to sit down and talk to him and video him because his story and its one we want. We want want them all.

[00:45:19] Angélica Cordero: Yeah, every single one that's left. There aren't that many that are left alive right now.

Kaye Ackermann: I think we're down to about probably fewer than 20,000.

Angélica Cordero: Wow. That's wild, because just a few years ago it feels like it was at 300,000.

[00:45:33] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah, that’s correct. But you know, the youngest, if they were, say 18 in 1945, they're still old.

[00:45:39] Laura Bailey: Yeah. Mm hmm. Yeah. And, you know, the veterans that are among us now were not, in no way trivializing what they saw, but they were the late arrivals. They were the late replacements in the war. And they saw a lot because it was as the momentum gained, it was hard, it was fast, and it was fierce. So, the ones that entered the war with America, those are the ones that are gone now, already gone.

[00:46:05] Kaye Ackermann: The ones that are, that are still alive now, like our friend Vern. I have another friend also named Vern who lives nearby and he's about the same age. And those men, yes, came in late. So they didn't see, for instance, the horror of the Battle of the Bulge, the horror of Normandy, but they did see the horror of the concentration camps.

[00:46:28] Angélica Cordero: Yeah.

[00:46:29] Kaye Ackermann: So it's a, it's a trade off.

[00:46:31] Laura Bailey: It really is.

[00:46:32] Angélica Cordero: It's all bad.

[00:46:32] Kaye Ackermann: It’s all bad.

[00:46:33] Angélica Cordero: Yeah. It's all bad.

[00:46:34] Laura Bailey: One last story I would like for Kaye to share. And I'm going to be cryptic in leading her to the one that I want because I don't want to give anything away. But there is one particular tanker that she and Joy VanMeesen had spent a lot of time, researching. And then, Kaye, when we were visiting Vern in his…

[00:46:55] Kaye Ackermann: Yes, I was sure.

[00:46:56] Laura Bailey: you know where I'm going with this?

[00:46:58] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah.

[00:46:59] Laura Bailey: Do you know which story I'm talking about? My whole point is that you bless so many people with your research. I felt like this was the war, in a small way, giving back to you that particular day. So, if you can tell the whole story, I would appreciate it.

[00:47:17] Kaye Ackermann: Yes. When I was going into the Luxembourg American National Cemetery, and I was walking past the Wall of the Missing on the way in and I just happened to, as I was walking, I saw this name, PFC Billy Wolf, 712th Tank Battalion, which was Dad's battalion. And I thought, “Oh gosh, he's on the Wall of the Missing. I don't know anything about this young man.” And so I stopped and looked at it and I took a picture of it and I went on. Then, my guide when I was over there was someone named Joey Van Meesen, great young man, terrific. He's with Footsteps Researchers. He reached out to me a couple times and he was just really curious about Billy Wolf.

I don't know why, but that's kind of struck up some interest and I looked online and I found a couple of things that Aaron Elson, the author I talked about, had interviewed. I think he had interviewed Billy's family at one point. He had identical twin sisters who were just younger than Billy. They had been able to tell Aaron Nelson some things, but he was missing in action. You know, he burned in the tank. That was the reality of World War II.

Well, whenever a tank was hit and it incinerated. Basically a lot of our tankers were cremated on the spot. So, they will always be missing in action, because we don’t have anything to give to the family. Anyway, over the years, it's just kind of this, I've had this Billy Wolf, young man from Virginia, in the back of my mind.

And so Laura and I were in Vern's garage. We were looking through things, books, notes, pictures, all sorts of stuff, and taking pictures of things. Just whatever we might need for our research. Then, Laura picked up something and handed it to me. And it was a block of wood and on the block of wood, it had several tank parts. And in the upper left-hand corner, it said “From the tank of Billy P. Wolf.”

[00:49:29] Angélica Cordero: What?

[00:49:30] Laura Bailey: I kid you not. Kid you not.

[00:49:34] Kaye Ackermann: And it was like I couldn't, I could not take a picture of that thing fast enough.

[00:49:41] Angélica Cordero: I bet.

[00:49:44] Kaye Ackermann: And send a message to the Netherlands where Joey Van Neeson is and, and tell him, “Joey, you're not going to believe this one?” Okay. And, you know, and just say, "Look at this.” And, and he was the same way I was. It was like, gosh, when you've got a name for a soldier and you put something together…and it's such a sad story. Yeah. But there it was.

[00:50:09] Laura Bailey: Angélica, you can cut this part if you want to. But when she held that, my first thought was the Big Bang Theory when Penny gave Sheldon the napkin that Leonard Nimoy used at the Cheesecake Factory. I don't know if you've ever seen that, but he immediately started shaking and sniveling a little. You couldn't have, it was just a wonderful, wonderful moment. But you were going to ask Kaye something.

[00:50:37] Angélica Cordero: Well, to the same, I guess, illustration that you just gave, I always think these moments to me are the exact things that actually fuel me as somebody who really likes history, to continue to keep trying to piece the puzzle pieces together. It so often feels like I'm constantly on a treasure hunt, which sounds probably maybe childish a little bit. There's just something unexplainable, I guess, when you just so happen to be in the right place at the right time, and the cosmos align, if you would say, and the thing that you've spent so long searching for and hunting for. Just kind of miraculously pops up. It's like its own kind of treasure of its own kind.

[00:51:27] Kaye Ackermann: Well, yeah, it's like when I realized that I had found the mass grave. I was just stunned for a moment. I just sat there and didn't do anything. I thought, “Gosh, that's from 1969.” And it was 2023. And finally I knew where it was. And I think I can say I knew without a question because my dad drove his tank right by it. And quite frankly, Laura's grandfather might've been riding on the tank.

[00:51:52] Angélica Cordero: That's I think the other aspect of it that probably adds a whole different element to how special that one moment is.

[00:52:01] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah. That was, that was cool.

[00:52:02] Angélica Cordero: Cool.

[00:52:03] Kaye Ackermann: Yeah.

[00:52:04] Laura Bailey: It is. The first day I met Kaye, we talked for hours, as I mentioned earlier, but there was one statement she made. She said, “Now that you're looking, get ready. Because the unexplained is going to happen more often than you realize, and there are going to be so many godwinks coming your way.” And she's exactly correct in that, and one of the pictures that, she's sharing that viewers will be able to see is a picture of her in New Orleans at the National World War II Museum.

You can buy the commemorative bricks there. Angélica, you you've seen my grandfather's and there's about 55, 000 the last time I looked at their website of those commemorative bricks and whenever I ask someone or whenever I find that someone's going to New Orleans I ask them to have a picture made with my grandfather's brick and it was no different when you were there Angélica. When Kaye went, she did the same thing for me but the beauty of it was she had had a um a brick placed, but she had not been able to visit it for her father. And so it was a dual mission. She was going to find my grandfather’s and her father’s. Well, you can see that out of 55,000 bricks, they are in close enough proximity to one another that you can touch them both at the same time.

[00:53:21] Angélica Cordero: Wow.

[00:53:22] Laura Bailey: And that was one of the godwinks, in my opinion, that she spoke of on that first day we met. And I still get cold chills when I look at the picture or think about the situation.

[00:53:31] Angélica Cordero: I bet. I bet. Well, it's unexpected. And those are the best moments.

[00:53:36] Laura Bailey: They are. They're priceless.

[00:53:39] Angélica Cordero: Just before we wrap up, Kaye, I thought I would ask you one last question. What advice do you have for descendants of the war?

[00:53:47] Kaye Ackermann: Am I making the assumption that they want to know what happened to their father, grandfather, uncle?

[00:53:54] Angélica Cordero: I'll leave that to Laura.

[00:53:56] Laura Bailey: Yeah. You speak about finding your soldier, if someone's listening to this and they know that their grandfather or now even their great grandfather or grandmother was in the war, how would you recommend they get started?

[00:54:11] Kaye Ackermann: One of the things that is a challenge right now is the fact that our archives in St. Louis, where the personnel records have traditionally been kept, are way behind [in fulfilling requests]. And so when they're way behind, that was one thing. It was bad enough because of COVID. And then with the issues with the fire on top of it, it's just been really tough.

I think there are about 250,000 requests behind as of last July. But what you can get is the honorable discharge. They have on their website that if you write in and, you do have to be like a direct descendant or a certain, a relation to the soldier, but if you write in and just ask for that, they guarantee that they will get it to you within 10 days. If you get it in 10 days. That's not bad, first of all, but secondly, there's a whole lot of information on the honorable discharge itself.

You can find, first of all, the date of entering and leaving service. You can tell what unit they were in when they were discharged, which very well may not be the unit that they served in during the time frame that they were in combat, but nonetheless, it's a starting point. You can start either at the beginning of their time in the service or you can start at the end. You can work forwards or backwards on it, but the other thing that you can get from that is you can see what campaigns they fought in.

I'll use Europe as an example. There were four or five campaigns in Europe. There was Normandy, Northern France, Central Europe, and that will be written on there. The medals that that soldier received will be on there. Whether or not they achieved certain things like, you know, they all take marksmanship, tests and whether they became a marksman or a sharpshooter or an expert marksman. That'll all be on there. So, it gives you a lot to start with.

From there, you can hire an independent researcher. There are a couple that I could suggest either Footsteps Researchers or another one called Golden Arrow Research. For a couple hundred dollars they will look up a bunch of information for you. Eventually, if you want to go this far, you can find out, through what's called the Morning Reports, where your soldier was every single day. And you can match those up with the After Action reports and find out what was actually going on—where your soldier was.

Like, I can read all about the Battle of Oberwambach when I go into the dad's battalion. But then I can turn around and go over to Laura's grandfather's unit, which is the 358th Infantry Regiment, because I know they were paired together and see what they were doing and get a really good composite view of that battle. You can get a whole lot. And I'm a big believer that everyone should go to Europe and see something that our soldiers did. Because it's incredible.

[00:57:03] Laura Bailey: It absolutely is. Well, Kaye, thank you very much for being with us. And more importantly, thank you for what you do. I don't take what you do lightly and I'm very grateful for what you do and what you've done for our family just in our puzzle that we're trying to put together.

But also, I believe, you're the perfect guest for our World War II podcast because our lens, that of the females, those that served during the war and those that continue serving in the war. And I believe that's exactly what you're doing because you're doing your best to secure this history and to move it forward, not only for the nation, but for the individual families as well. So thank you very, very much.

[00:57:45] Kaye Ackermann: Well, thank you for having me. I've enjoyed it.

[00:57:47] Carys Caffarel: Hey everyone, Carys here. I just wanted to give a special thanks to Kaye Ackerman for sharing her personal history and insight with us today. As is true with all World War II historians, she would want you to ask those questions. Ask your families, look deep within your lives while the memories and heirlooms are relatively recent.

It's important we understand and secure the impact of the Second World War. Within each of our lives.

And thanks to you, of course, our listeners for tuning in.

Make sure to connect with us, follow us on Instagram [at] worldwarshe. Subscribe to our newsletter on Substack worldwarshe [dot] substack [dot] com.

Do you have a topic you want us to get into? We would love to hear from you as well as any feedback you might have. You can shoot us an email at worldwarshepodcast [at] gmail [dot] com.

As always, make sure to stay tuned as we receive our next set of orders to share with you all. Signing off for now.

Share this post